|

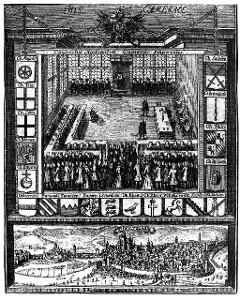

The Courts of the Holy Roman Empire A. High Courts of the Empire: The Reichskammergericht The Reichskammergericht (Camerae Imperialis Judicium), Imperial Chamber Court, was created at the Worms Reichstag of 1495. Its initial purpose was to sit in judgment of violations of the Landfrieden of 1495, but over time became the main court of the Empire and the guarantor of imperial law. The Court consisted initially of a Judge assisted by 16 assessors (a number increased to 50 in 1648 and reduced to 25 in 1729). The Judge, two Presidents and one assessor were appointed by the Emperor, the other assessors by the electors and by the circles of the States of the Empire. The Judge was noble, or rank no less than a baron. Half of the assessors were noblemen, the others were doctors of law. The Judge, one President and 13 assessors were catholics, the other President and 12 assessors were protestants (Augsburg confession). The members, once appointed, were reichsunmittelbar and could not be removed except by the Court itself. The court also had 12 advocates and 30 procurators to process cases. Cases were examined by "senates" of 8 or 9 members, with equal numbers of protestants and catholics. When the senate was split evenly, additional members were appointed, or the case was sent to the full Court. In religious matters, members voted by religion (a procedure called itio in partes). If votes remained evenly split, the matter was sent to the Reichstag. On some procedural matters the Court could make interim rulings that had force of law until an imperial law was published. The Court was competent in suits against immediate members of the empire, either in first or second instance; in civil matters involving mediate members of the empire, as appeals court from local courts (except when there was privilegium de non appellando, as for territories of electors); appeals on denials of justice; it could also confirm treaties, testaments, guardianships among immediate members. It had no jurisdiction over spiritual matters (including validity of marriages), cases involving major fiefs or matters of imperial grace, criminal cases involving immediate members. The court had exclusive jurisdiction over judicial matters involving its own members. One could ask the Court to review its own rulings, or refer the matter to a Reichskammergerichtsvisitation, a commission appointed by the Reichstag to periodically review the Court's activities (initially annual, these visitations became scarcer after the 16th c.). Ultimately, it was always possible to appeal to the Reichstag itself.

The Reichshofrath Maximilian I had only reluctantly agreed to the formation of the Reichskammergericht. To help him in his direct administration of justice, he established in 1518 a Reichshofrath (Consulium imperiale aulicum), Imperial Court or Aulic Council, which became accepted as equal to the Reichskammergericht in 1648. Contrary to the Court, this body was a creature of the Emperor. It had a president, a vice-president, and 16 councillors, all appointed by the Emperor. The imperial vice-chancellor, appointed by the arch-chancellor (the elector of Mainz) was also a member ex officio, and presided in the absence of the president. (The vice-chancellor and the president were the only Imperial Ministers). Members of the Council had to be German nationals, and the president and vice-president had to be noblemen of the empire (prince, count or baron). Members could not be removed except by a ruling of the Council itself, but the death of the emperor automatically brought the dissolution of the council and the imperial chancery. The Council had two functions:

The Council had essentially the same jurisdiction as the Court, and it was up to the plaintiff to choose where to file his suit. There were other matters in which only the Council was competent; and there were matters where the Court's jurisdiction was acknowledged but which were routinely handled by the Council. Such was the case of criminal cases involving immediate members, and cases involving imperial favors or concessions. All matters were decided by the whole Council. In case of split votes, the president could break the tie, or he could choose to refer the matter to the Emperor. In religious matters, an even split automatically referred the matter to the Reichstag. Appeals were handled the same way as for the Court, except that the right of visitations, in principle held by the arch-chancellor (elector of Mainz) were never exercised.

|