|

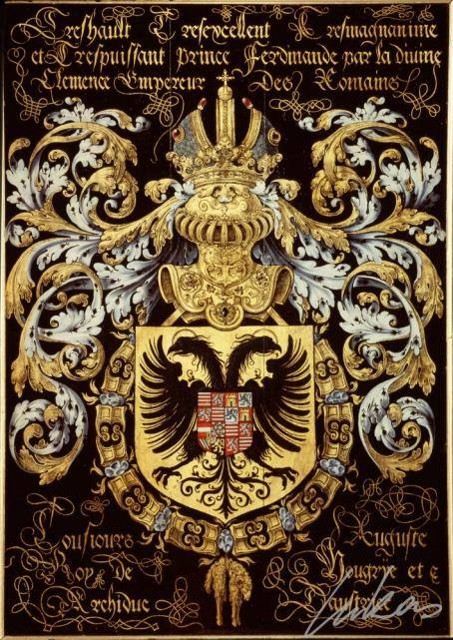

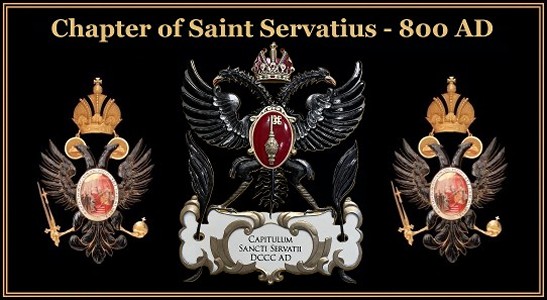

The Chapter of Saint Servatius - Grand Provost of the Chapter of Saint Servatius of the Holy Roman Empire The Chapter of Saint Servatius was a college of secular clergy, which was associated with the Saint Servatius in Maastricht from the Middle Ages until the end of the Ancien Regime. The secular chapter experienced its greatest heyday during the High Middle Ages, but it also remained the most powerful and richest spiritual institution in Maastricht and the surrounding area, until its abolition in the year 1797.

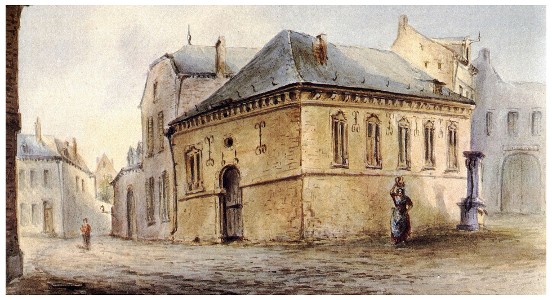

The Palace of the Grand Provost of the Chapter of Saint Servatius. The Chapter of Saint Servatius was re-established on 12th October 2023. The mission of the Chapter of Saint Servatius is to preserve, promote, and make accessible to a wide audience the historical, liturgical, and cultural heritage of the Chapter, the Saint Servatius Basilica and the Holy Roman Empire. We aim to promote the values of the Roman Catholic Faith and the Catholic Social Teaching and it’s unique heritage as a source of inspiration, education, and connection for both the local community and visitors from afar. Our vision is to be a dynamic center for cultural, educational, and spiritual activities, anchored in the rich history of the Chapter of Saint Servatius. By (co-) operating a wide range of facilities, including a museum, an art gallery, an experience center, and organizing events, excursions, and tours, we aim to create a vibrant meeting place in the “Palace of the Grand Provost of the Chapter of Saint Servatius” at Henric van Veldekeplein number 29. We will implement innovative ways to share and celebrate our heritage, while respecting the traditions that form our foundation. Through collaboration with other organizations and institutions, and by encouraging the promotion of art and friendship circles, we strive to fulfill the mission of the Chapter and unite the past, the present and the future. In close cooperation with all residents, organizations, and institutions, on and around Henric van Veldekeplein, especially the church boards of the Saint Servatius Parish, Saint John, the Treasury Board of Saint Servatius, the Board of the “Sisters of Charity of St. Charles Boromeo”. Website of the Chapter: www.kapittelvansintservaas.nl

The Origin of Chapter (before 1000) The Chapter of the Saint Servatius Church in Maastricht probably originated from a monastic community that had settled near the burial church of Saint Servatius in the early Middle Ages. The Carolingian scholars Alcuin and Einhard are both mentioned as lay abbots of Saint Servatius Abbey. The monastery was probably converted into a chapter of secular canons in the 9th century. The canons then still lived a communal life that was dominated by choir prayer, shared meals (in the refectory) and shared dormitories (dormitories), but - unlike monks - had private property. At the head of the chapter was the provost. The dean was concerned about the spiritual welfare of the canons. The provost initially lived opposite the church in the provost of Sint-Servaas. This was connected to the westwork of the church by a covered wooden walkway, so that the provost could enter his private chapel (Saint Agatha's chapel) in the westwork unseen. The canons had their own chapel in the Double Chapel (now Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius), located north of the transept, accessible from the cloister of the church. In the upper chapel there was a chapel and the chapter house, on the ground floor the repository of the church treasury. A few provosts and deans were also buried in the lower chapel. At least five provosts were buried in the nave of the church.

Through donations from kings, rulers and private individuals, the chapter soon amassed considerable wealth, largely consisting of real estate. The proceeds were divided into prebends, of which about forty canons were maintained. The chapter leased the lands (approx. 2000 ha) and received grain as payment, which was stored in a large barn next to the mountain portal of the Sint-Servaaskerk ('t Spijker). In addition, the chapter owned several vineyards in Germany. On other pieces of land, which the chapter did not own, tribute had to be paid in the form of an amount of money and (sometimes) a few capons. The canons were paid the attendance fee from the dues, an allowance for their presence at the choir services. The oldest mention of a donation to the Church of Saint Servatius dates from 779. Most of the possessions were acquired before 1050, but it is usually impossible to find out how and when they came into the possession of the chapter. The land belonging to the chapter of Sint-Servaas stretched from what is now North Brabant and the area around Leuven to the Rhine, Moselle and Ahr. The core area was in the current Belgian province of Limburg, west of Maastricht. The most important part of this core area formed the so-called Eleven Banks of Sint-Servaas, where the chapter held not only the land and the associated rights, but also the jurisdiction over the inhabitants. Vlijtingen was the main bank of the areas to the left of the Maas. Here the chapter owned the castle Daelhof and the Blockhuis, the residence of the riding consort (both disappeared). The steward's house of the Rijproost in Zepperen has been preserved. One of the banks, Tweebergen, was partly within the city walls of Maastricht and partly outside. The name Proosdijveld in the Mariaberg district is a reminder of this.

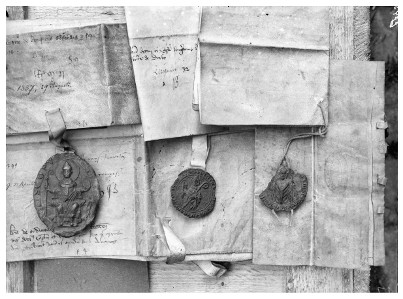

Seals And Coins: seal of the chapter of Saint Servatius on a charter of 1337. The Chapter (1000-1200) In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Saint Servatius Chapter reached the pinnacle of its power. The ties between the Reich Church and the German kings were close and several provosts held the office of Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire. The provosts almost without exception came from the highest circles of the German nobility and often combined their position in Maastricht with other honorable jobs, such as the provostship in Aachen, Cologne or Bonn, or later became (arch)bishop of Liège, Cologne or Mainz. In 1204, the right of appointment of the provosts passed to the duke of Brabant, after which the importance of the chapter declined somewhat. In this period the canons said goodbye to communal life and went to live independently. The canons' houses of the Sint-Servaas chapter were located in a continuous area around the Sint-Servaaskerk, mainly on the Vrijthof, the Sint Servaasklooster, the Henric van Veldekeplein and the Keizer Karelplein. In this area, the claustral canal or immunity of the chapter, there were also the Sint-Janskerk (the baptismal and parish church), the Sint-Servaasgasthuis and the Sint-Jacobskapel (where pilgrims were received and the sick were cared for), the deanery , the bakery, the brewery, the storehouses and the horse stables of the chapter. Judgment took place in the 'long corridor' of the cloister, executions took place behind the deanery at the wall of the first rampart, the border of immunity. Convicts from the eleven banks of Sint-Servaas were locked up in the Burght van Heer. In addition to its own collegiate church (Sint-Servaas), the chapter also exercised authority over two parish churches in Maastricht (Sint-Janskerk and Sint-Matthijskerk) and seven neighborhood or kerspel chapels (Sint-Jacob, Sint Joris, Heilige Geest, Sint-Amor, Wittevrouwen, Sint-Catharina en Sint-Antonius; all demolished). In addition, the chapter owned parish churches in more distant villages (perhaps once founded from the diocese of Maastricht), of which the chapter held the collation and was entitled to the tithe.

Canons of Saint Servatius in Winter and Summer Costumes, ca. 1700. The Chapter (1200) In 1232, under provost Otto van Everstein, a division of property took place between the chapter and the deanery of Saint Servatius, whereby the provost was assigned two prebends and the canons were allowed to divide the remaining prebends. From 1330 the dean was also entitled to two prebends. In the 18th century, the annual income of a prebend was estimated at 750 Dutch guilders. Of the eleven benches of Sint-Servaas, two were assigned to the provost in 1232; the remaining nine lordships were under the administration of the chapter. The chapter also kept the income from the ban mills. The toll over the Maasbrug was divided; after deducting the cost of repairs, half of the proceeds went to the provost, the other half to the chapter. In 1646 the chapter handed over the bridge to the city, because the maintenance became too expensive. After 1632, the right to appoint the provosts passed from the Duke of Brabant to the States General of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. At that time the provostship was sold to the highest bidder. Nevertheless, the chapter held on to the immediacy of the kingdom; directly dependent on Pope and Emperor and independent of Prince-Bishop and States-General. As a result, the claustral area of ??Sint-Servaas, where the chapter and everyone who belonged to it enjoyed immunity, remained a kind of state within the city. Until the abolition of the chapter, legal battles were fought over the powers of the chapter and the States General. The chapter was also unable to prevent St. John's Church, located within the claustral canal, from having to be ceded to the Protestants in 1633. In the period after the Reformation, the chapter of Saint Servatius consisted of approximately 190 members (not including serving staff): a provost, a dean, 36 canons ordinary, 30 'minor' canons (chaplains, who dedicated masses at the various altars of the Sint-Servaaskerk), about 100 other chaplains, 10 rod bearers (court officers and bailiffs) and 12 chorisocii (guides at processions). The original purpose of the chapter was to worship God and care about the 'church of Maastricht', but that ideal had become clouded over time. From 1545-1563, the Council of Trent attempted to put an end to a series of abuses in the Roman Catholic Church. The chapter of Saint Servatius also had to deal with this and in 1556, 1557, 1559 and 1609 the canons were visited by visitation committees (in 1557, among others with the Leuven professor and inquisitor Ruard Tapper). After this, the chapter was urged to pay more attention to matters such as attending choir prayers, not chatting, laughing or arguing in the choir, wearing the tonsure and clerical robes, the prohibition of games of chance or inn visits, compulsory living within the claustral girth and the removal of concubines and illegitimate children from the area. During the last visitation, the worst abuses appeared to have been resolved. At the end of the 18th century, some canons once again lived outside the claustral canal. For example, the brothers Andreas and Wilhelmus Soiron had a large mansion built on the Grote Gracht after a design by their brother, the architect Mathias Soiron. The provost of the chapter (also known as high provost) no longer lived in the deanery, but in a luxurious city palace on Henric van Veldekeplein. The provosts also had a castle in Mechelen-aan-de-Maas, the Hof van Oensel.

Horse stable of the chapter, after 1797 of the garrison, Keizer Karelplein. End of the Chapter After the conquest of Maastricht by the French Revolutionary armies in 1794, the chapter initially received heavy war levies. To this end, a large part of the church treasure was sold or melted down. In the end this was of no avail: in 1797 the chapter and deanery were abolished. The final cheers, T.W.J. Baron van Wassenaar Warmond, was captured and deported to France because he refused to take the oath of allegiance. All property of the church and chapter reverted to the state. The estates leased by the chapter and deanery (a total of about 2000 hectares) were also sold at public auction. The church was used as a stable for horses by the French garrison and was not given a religious function again until 1804. After the French Period, provost Van Wassenaar Warmond made unsuccessful attempts to restore the chapter. The last canon died in 1858 at the age of 84 in Sint-Truiden.

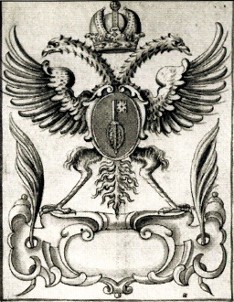

Deanery of Saint Servatius, administrative center of the chapter. Heritage of the Chapter The most important building that recalls the chapter is of course the Basilica of Saint Servatius. In particular, the priest's choir (where the canons sat in choir stalls attended the choir prayers several times a day), the Double Chapel (with the chapter house and the funerary and private chapel of the chapter) and the cloister of the Basilica of Saint Servatius (with, among other things, the refectory , today's Day Chapel) were places primarily intended for the canons. In the cloister was also the Kapittelschool van Sint-Servaas, now used as a sacristy. Around the church, the Sint-Janskerk, the Sint-Servaasproosdij, the provost's palace and at least fifteen canons' houses form the main heritage of the chapter. The oldest canons' house - and also a place to stay for high guests - is the Spanish Government; the youngest canons' house is Huis Soiron, located outside the claustral canal, built a few years before the abolition of the chapter. A copy of the missing immunity posts that bordered the claustral canal until 1797 can be seen in the courtyard of the Sint Servaasklooster building 32. On the hard stone post you can see a relief of the key of Saint-Servatius, the hallmark of the chapter. Modern lampposts on the Vrijthof bear images of the crowned eagle, which also refers to the chapter coat of arms. Names such as Sint Servaasklooster and Kanunnikencour (near Henric van Veldekeplein), Proosdijweg and Proosdijveld (both in the Mariaberg district), and Kapittellaan (in Heugem) also refer to the chapter. Outside Maastricht, the churches of Saint Servatius, Monulfus and Gondulfus in particular remind us of the influence that the Maastricht chapter had in a large area, especially in the Eleven Banks of Sint-Servaas. De Burght is located in Heer, formerly the prison of the chapter. The caretaker's house of the chapter is still present in Zepperen.

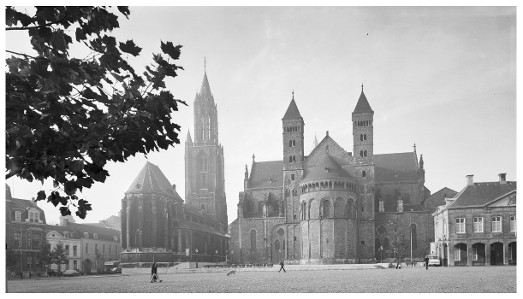

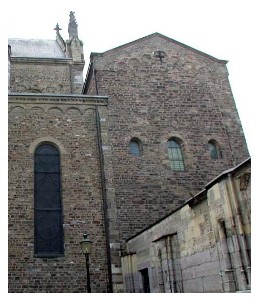

The Basilica of Saint Servatius The Basilica of Saint Servatius is a Roman Catholic church dedicated to Saint Servatius, in the city of Maastricht, the Netherlands. The architecturally hybrid but mainly Romanesque church is situated next to the Gothic church of Saint John, backing onto the town's main square, Vrijthof.

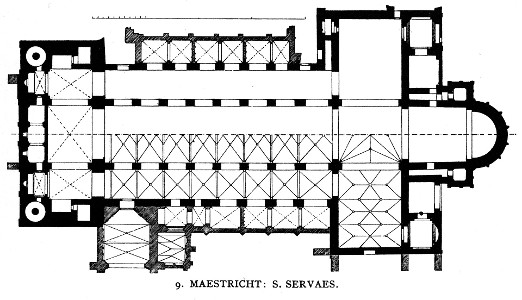

History of the Basilica of Saint Servatius The present-day church is probably the fourth church that was built on the site of the grave of Saint Servatius, an Armenian missionary who was bishop of Tongeren and died allegedly in 384 in Maastricht. A small memorial chapel on the saint's grave was replaced by a large stone church built by bishop Monulph around 570. This church was replaced by a larger pilgrim church in the late 7th century, which was then replaced by the present-day structure, which was built in several stages over a period of more than 100 years. The nave was built in the first half of the 11th century, the transept in the second half of the century, and the choir and westwork in the 12th century. The Romanesque church was built during a period in which the chapter of Saint Servatius kept close ties to the Holy Roman Emperors, which resulted in a building that has the characteristics of a German imperial church. The dedication of the church in 1039 was attended by the emperor Henry III and twelve bishops. Most of the church's Medieval provosts were sons of the highest ranking German noble families. Several held the office of chancellor of the German Empire, at least eight provosts went on to become archbishops.

The sculpted Bergportaal, at the south side of the church, was begun around 1180 and can be considered late Romanesque or early Gothic. All the chapels along the side aisles are Gothic (14th and 15th centuries), and so is the vaulted ceiling of the nave and the transept. In 1556 a late Gothic spire was added onto the westwork between the two existing towers. In 1770 the entire westwork was crowned with Baroque helmet spires, designed by the Liège architect Etienne Fayen. Over the centuries the interior of the church underwent many changes. In the 17th century, the Gothic choir rood screen with sculpted depictions of the life of Servatius was demolished. Fragments from the 14th-century screen were discovered during the 1980s restoration works and are now kept in the church's lapidarium in the East crypt. By the end of the 18th century, the entire church interior had been painted white, the colourful Medieval stained glass windows had been replaced by colourless glass, and the church looked distinctly Baroque. The north transept holds some epitaphs, of which the one for Egidius Ruyschen in Renaissance style is probably the most original. Nearby is the impressive tomb of the Count and Countess van den Bergh (Johannes Bossier, 1685), which was transferred from the Dominican church of Maastricht. From the Dominican church were also transferred the ornate confessionals by Daniël van Vlierden (Hasselt, 1700), which are located in various parts of the church. In 1797 the chapter was dissolved by the French revolutionaries and the church was used as a horse stable by the troops. The furnishings of the church were sold, stolen or trashed. Likewise, most of the church treasures disappeared during the first years of the French occupation. In 1804 the church was returned to the parish but the building was an empty ruin. It was during the period that followed that most of the damage was done. The 11th-century Chapel of Saint Maternus and the 15th-century Koningskapel (built by the French kings Charles VII and Louis XI) were considered irreparable and were demolished. For liturgical reasons, it was deemed necessary to lower the elevated choir, for which the underlying 11th-century crypt was demolished. In 1846 the four panels that belonged to the reliquary chest of Saint Servatius (Noodkist) were sold to an antiques dealer and ended up in the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels. Between 1866 and 1900 the church underwent major restorations during which some of the damage done earlier in the century was reversed. The restoration was led by famous Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers. In 1955 a fire caused Cuypers' Gothic Revival westwork spire to fall through the roof of the church, which made another thorough restoration necessary (1982–1991). During this latter restoration, Cuypers' colourful interior decoration scheme was largely removed. During this most recent restoration, extensive excavations that were carried out in the church and adjacent buildings, revealed a wealth of information about the history of the church and its predecessors.

Religious significance Through the ages, the presence of the grave of Saint Servatius in the church crypt and the many relics in the church treasury, have drawn large numbers of pilgrims. Starting in the 14th century (but perhaps earlier) a seven-yearly pilgrimage was organized in cooperation with nearby Aachen Cathedral and Kornelimünster Abbey, attracting tens of thousands of visitors to the region. This Pilgrimage of the Relics (Dutch: Heiligdomsvaart) continued until 1632 when Maastricht became affiliated with the Dutch Republic (Capture of Maastricht). The Pilgrimage of the Relics was revived in the 19th century and the tradition continues in our days. The most recent Pilgrimage of the Relics took place from May 24 to June 3, 2018.

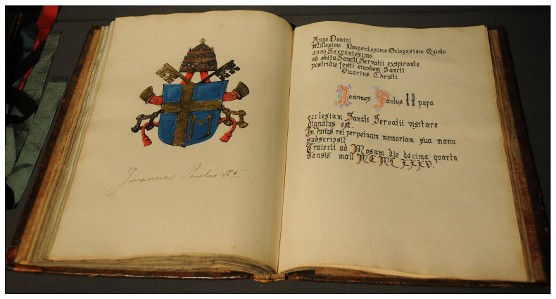

Today, the Basilica of Saint Servatius is the main church of the Deanery of Maastricht, which belongs to the Diocese of Roermond. The church continues to be a center of Catholicism in Maastricht (the other main church being the Basilica of Our Lady). The church was made a Basilica Minor by Pope John Paul II during his visit in 1985.

Art historical significance Although the present building conveys a rather hybrid image of architectural styles, the church of Saint Servatius is considered to be one of the most important religious buildings in the former Prince-Bishopric of Liège. Both the East choir and the Westwork of the Maastricht church have been influential in the development of Romanesque architecture in the Meuse and Rhine valleys. Several authors have pointed out the significance of the South portal's late Romanesque sculpture for the early development of Gothic sculpture in France.

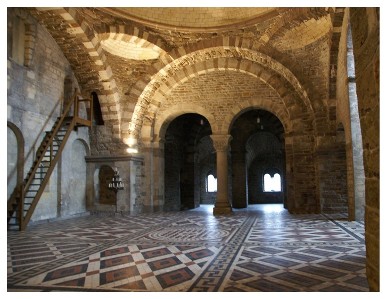

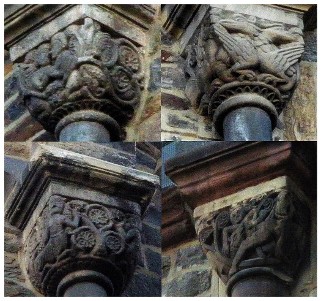

Romanesque sculpture Both the exterior of the East choir and the interior of the westwork of Saint Servatius contain architectural sculpture that is considered amongst the most interesting in the Mosan region. The 34 elaborately carved capitals in the Westwork depict scenes from books well-known to the canons, such as Saint Augustine's De Civitate Dei and various bestiaries. Recurrent themes are: botanical ornaments, animals, humans fighting with animals, humans entangled in plants, and humans engaged in daily activities. A close relationship has been established by art historians between the Maastricht Westwork capitals and those of the East choir of Our Lady's in Maastricht, the Rolduc crypt, the dwarf gallery of the Doppelkirche Schwarzrheindorf (Bonn), and the Wartburg palace (near Eisenach).

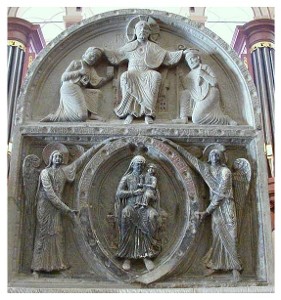

Also in the Westwork of Saint Servatius is a sculpted Romanesque choir screen, also referred to as the double relief. The lower rectangular part depicts the Virgin and Child in a mandorla held by two angels, the upper part shows Christ handing over the keys of Heaven to Saint Peter and Saint Servatius. The relief closely relates to a choir screen in Saint Peter's in Utrecht. Elsewhere in the church a 12th-century tympanum depicting the Majestas Domini can be found as part of a former portal. The choir ceiling shows remnants of ceiling paintings, depicting the visions of Zechariah. This may be the only surviving work by a once important group of Maastricht and Cologne based painters, who received high praise from Wolfram von Eschenbach in his Parzival. The church's South portal (Bergportaal) contains sculpture that marks the period of transition between late Romanesque and early Gothic sculpture. The sculpted tympanum and the two inner archivolts date from around 1180 and are Romanesque is style, the rest of the portal can be considered Gothic and dates from around 1215.

Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius The Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius is a museum of religious art and artifacts inside the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht, Netherlands. The treasure of the church of Saint Servatius was put together over many centuries. One of the oldest pieces (today non-existent) was a reliquary in the shape of a triumphal arch, donated by Einhard (biographer of Charlemagne and abbot of Saint Servatius) in the 9th century. In the 11th century a custodian ('custos') was put in charge of the church's already seizable treasure.

During the late Middle Ages the number of relics further increased. A septennial Pilgrimage of the Relics (Dutch: Heiligdomsvaart) attracted tens of thousands of pilgrims. At these occasions, the main relics were shown to the pilgrims gathered in Vrijthof square from the dwarf gallery. In 1579, the church treasure suffered badly during the Sack of Maastricht by the Spanish troops led by the Duke of Parma. In 1634, under the threat of war, the treasure was brought to Liège, where it remained for twenty years.

After the conquest of Maastricht by the French in 1794, the chapter of Saint Servatius was made to pay heavy war taxes. In order to pay these taxes gold and silver artefacts from the church treasure were melted down or sold. In 1798 the chapter was dissolved. A few important pieces had been brought into safety by the canons, some of which were given back after the church was restored to the religious service in 1804, but other pieces could not be retrieved. Some of the church's former treasures can now be found in museums and libraries around the world, such as the National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague, the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum in New York. The present treasure of the Basilica of Saint Servatius therefore, is much smaller than it once used to be.

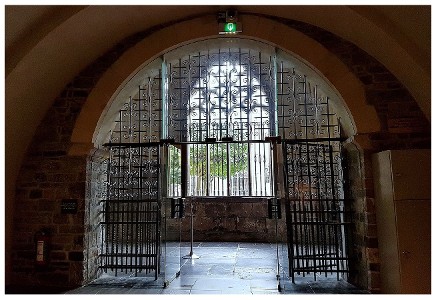

The Building In 1340 it was reported that the treasure of the church was kept in a dark vaulted room on the lower floor of what is called the double chapel. The double chapel is one of the oldest surviving parts of the church and dates back to the 11th century. It was built adjacent to the northern transept and can only be accessed via the cloisters. This seems to have been the permanent location of the treasury until 1873, when it moved to the former refectory and chapter school.

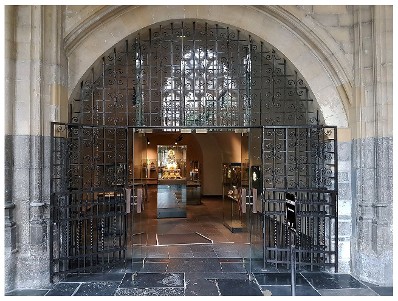

After the restoration of the double chapel in 1982, the treasury was once again housed in its original location. The treasury now occupies both floors of the double chapel and a side room on each level. The basement floor with archaeological excavations has been made accessible. The entrance to the treasury, via the East wing of the cloisters, is on Keizer Karelplein, which is also the main entrance to the church.

The Collection The treasure of the Basilica of Saint Servatius traditionally consists of four parts: 1. the so-called Servatiana, objects traditionally associated with the life of Servatius, 2. relics and reliquaries, 3. liturgical implements and 4. ancient fabrics. The church's art collection and various archaeological finds are not part of the treasure but are also exhibited in the museum.

Servatiana The key of Saint Servatius: decorative key, one of the attributes of the saint, silver (early 9th century). Pectoral cross of Saint Servatius: silver and golden cross (wooden core), with enamel and gemstones (10th or 11th century), a gift to the church from the duke of Bavaria. The cup of Saint Servatius: millefiori glass, Roman (1st century). The Crozier of Saint Servatius: wooden staff with ivory crook (12th century). Portable altar of Saint Servatius: green serpentine stone with silver ornaments (12th century).

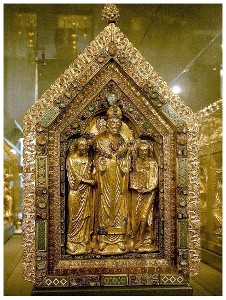

Reliquaries The 'Noodkist': the reliquary shrine of Saint Servatius, an oak wooden chest, covered with gilded copper and decorated with enamel, vernis brun, cabochons and filigree (±1160). The 'Noodkist' was originally positioned on the main choir of the church and was accompanied by four panels, that in 1843 were sold and are now in the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels.

The portrait bust of Saint Servatius: reliquary bust containing the skull of the saint, donated by Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma after the Sack of Maastricht (1579) in which the original bust was largely lost.

Liturgical implements This part of the treasure suffered most during the French period (1794-1814). Many chalices, patens, monstrances and other liturgical objects made of gold or silver were melted down in order to pay the war taxes that the French demanded from the canons. However, a few liturgical vessels from the Middle Ages survived and quite a few from the Baroque period (notably some Maastricht silver pieces) are still in the collection.

Textiles The medieval textiles collection of the Basilica of Saint Servatius is counted among the most important of its kind. From 1989 till 1991 the textiles were carefully restored and documented by specialists from the Swiss Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg. Among the best pieces in the collection are the so-called albe of Saint Servatius and the robe of Monulph. Furthermore, there is an extensive collection of early-Medieval woven silks (some dating back to the 7th century) from Constantinople, Egypt and Central Asia and various medieval woven materials from the Meuse-Rhine area, Spain, Italy and the Middle East.

Art collection The art collection of the Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius consists of a modest collection of paintings, prints, illuminated manuscripts, wood carving, stone sculptures, alabaster and ivory carving, enamels, and gold and silver smithing.

Archaeology Archaeological excavations took place in the double chapel in 1981-82. Underneath the ground level floor of the Sacrarium inferior canons' grave stones were found, some dating back to the 13th century. Also, parts of walls were excavated that at the time were interpreted as the remains of a Carolingian polygonal church. As it turned out, the walls belonged to polygonal transept arms of a 10th or 11th century church. These remains can be seen in the basement underneath the treasury. Part of the archaeological collection is on display in the lapidarium in the eastern crypt. An important find was the 1086 funeral cross of Humbert, who was provost of the chapter of Saint Lambert's Cathedral in Liège and Saint Servatius in Maastricht. It was he who had the double chapel built which is today the church treasury. +

|