|

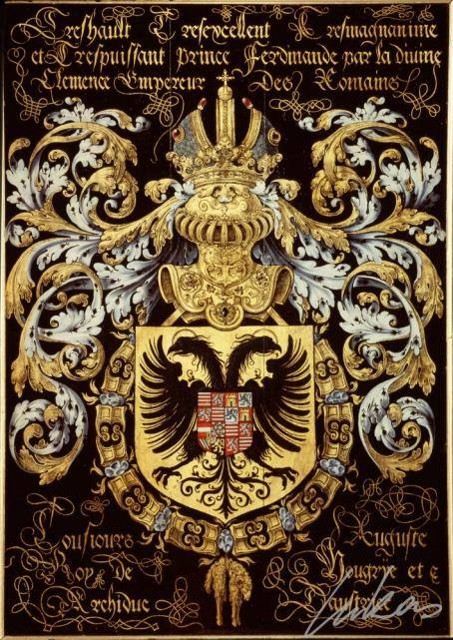

The Peace of Westphalia - 1648 The Peace of Westphalia (German: Westfälischer Friede) was a series of peace treaties signed between May and October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster effectively ending the European wars of religion. These treaties ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) in the Holy Roman Empire, and the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) between Spain and the Dutch Republic, with Spain formally recognizing the independence of the Dutch Republic. The peace negotiations involved a total of 109 delegations representing European powers, including Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, Philip IV of Spain, the Kingdom of France, the Swedish Empire, the Dutch Republic, the Princes of the Holy Roman Empire and sovereigns of the free imperial cities. The treaties that comprised the peace settlement were: The Peace of Münster between the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of Spain on 30 January 1648, ratified in Münster on 15 May 1648; and Two complementary treaties both signed on 24 October 1648, namely:The Treaty of Münster (Instrumentum Pacis Monasteriensis, IPM), between the Holy Roman Emperor and France and their respective allies. The Treaty of Osnabrück (Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis, IPO), involving the Holy Roman Empire, Sweden and their respective allies. The treaties did not restore peace throughout Europe, but they did create a basis for national self-determination. The Peace of Westphalia established the precedent of peaces established by diplomatic congress, and a new system of political order in central Europe, later called Westphalian sovereignty, based upon the concept of co-existing sovereign states. Inter-state aggression was to be held in check by a balance of power. A norm was established against interference in another state's domestic affairs. As European influence spread across the globe, these Westphalian principles, especially the concept of sovereign states, became central to international law and to the prevailing world order. Locations Peace negotiations between France and the Habsburgs, provided by the Holy Roman Emperor and the Spanish King, were started in Cologne in 1641. These negotiations were initially blocked by France. Cardinal Richelieu of France desired the inclusion of all its allies, whether sovereign or a state within the Holy Roman Empire. In Hamburg and Lübeck, Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire negotiated the Treaty of Hamburg. This was done with the intervention of Richelieu. The Holy Roman Empire and Sweden declared the preparations of Cologne and the Treaty of Hamburg to be preliminaries of an overall peace agreement. This larger agreement was negotiated in Westphalia, in the neighbouring cities of Münster and Osnabrück. Both cities were maintained as neutral and demilitarized zones for the negotiations. Münster was, since its re-Catholization in 1535, a strictly mono-denominational community. It housed the Chapter of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster. Only Roman Catholic worship was permitted. No places of worship were provided for Calvinists and Lutherans. Osnabrück was a bidenominational Lutheran and Catholic city, with two Lutheran and two Catholic churches for its mostly Lutheran burghers and exclusively Lutheran city council and the Catholic Chapter of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück with pertaining other clergy and also other Catholic inhabitants. In the years of 1628–1633 Osnabrück had been subjugated by troops of the Catholic League. The Catholic Prince-Bishop Franz Wilhelm, Count of Wartenberg then imposed the Counter-Reformation onto the city with many Lutheran burgher families being exiled. While under Swedish occupation Osnabrücks's Catholics were not expelled, but the city severely suffered from Swedish war contributions. Therefore, Osnabrück hoped for a great relief becoming neutralised and demilitarised. Both cities strove for more autonomy, aspiring to become Free Imperial Cities, so they welcomed the neutrality imposed by the peace negotiations, and the prohibition of all political influence by the warring parties including their overlords, the prince-bishops. Since Lutheran Sweden preferred Osnabrück as a conference venue, its peace negotiations with the Empire, including the allies of both sides, took place in Osnabrück. The Empire and its opponent France, including the allies of each, as well as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and its opponent Spain (and their respective allies) negotiated in Münster. Delegations The peace negotiations had no exact beginning and ending, because the participating total of 109 delegations never met in a plenary session, but arrived between 1643 and 1646 and left between 1647 and 1649. Between January 1646 and July 1647 probably the largest number of diplomats were present. Delegations had been sent by 16 European states, sixty-six Imperial States, representing the interests of a total of 140 involved Imperial States, and 27 interest groups, representing the interests of a variety of a total of 38 groups. The French delegation was headed by Henri II d'Orléans, duc de Longueville and further comprised the diplomats Claude d'Avaux and Abel Servien. The Swedish delegation was headed by Count Johan Oxenstierna (son of Chancellor Count Axel Oxenstierna) and was assisted by Baron Johan Adler Salvius. The head of the delegation of the Holy Roman Empire for both cities was Count Maximilian von Trautmansdorff; in Münster, his aides were Johann Ludwig von Nassau-Hadamar and Isaak Volmar (a lawyer); in Osnabrück, his team comprised Johann Maximilian von Lamberg and Reichshofrat Johann Krane, a lawyer. Philip IV of Spain was represented by a double delegation. The Spanish delegation was headed by Gaspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán, and notably included the diplomats and writers Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, and Bernardino de Rebolledo. The Burgundian lawyer Antoine Brun represented Philip as hereditary ruler of the Franche Comté and the Spanish Netherlands. The papal nuncio in Cologne, Fabio Chigi, and the Venetian envoy Alvise Contarini acted as mediators. Various Imperial States of the Holy Roman Empire also sent delegations. Brandenburg sent several representatives, including Vollmar. The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands sent a delegation of six (including two delegates from the province of Holland (Adriaan Pauw) and Willem Ripperda from one of the other provinces; two provinces were not present). Johann Rudolf Wettstein, the mayor of Basel, represented the Swiss Confederacy.

Tenets The main tenets of the Peace of Westphalia were: All parties would recognize the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, in which each prince would have the right to determine the religion of his own state, the options being Catholicism, Lutheranism, and now Calvinism (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio). Christians living in principalities where their denomination was not the established church were guaranteed the right to practice their faith in public during allotted hours and in private at their will. General recognition of the exclusive sovereignty of each party over its lands, people, and agents abroad, and responsibility for the warlike acts of any of its citizens or agents. Issuance of unrestricted letters of marque and reprisal to privateers was forbidden. There were also territorial adjustments: The independence of Switzerland from the Empire was formally recognized; these territories had enjoyed de facto independence for decades. The majority of the Peace's terms can be attributed to the work of Cardinal Mazarin, the de facto leader of France at the time (the king, Louis XIV, being a child). Not surprisingly, France came out of the war in a far better position than any of the other participants. France retained the control of the Bishoprics of Metz, Toul and Verdun near Lorraine, received the cities of the Décapole in Alsace (but not Strasbourg, the Bishopric of Strasbourg, or Mulhouse) and the city of Pignerol near the Spanish Duchy of Milan. Sweden received an indemnity of five million talers, used primarily to pay its troops. Sweden further received Western Pomerania (henceforth Swedish Pomerania), Wismar, and the Prince-Bishoprics of Bremen and Verden as hereditary fiefs, thus gaining a seat and vote in the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire as well as in the respective circle diets (Kreistag) of the Upper Saxon, Lower Saxon and Westphalian circles. However, the wording of the treaties was ambiguous: Whether or not the city of Bremen was included in Swedish Bremen-Verden remained disputed. Facing the Swedish take-over, Bremen had claimed Imperial immediacy, which was granted by the emperor and thus separated the city from the surrounding bishopric with the same name. Sweden understood that Bremen was nevertheless to be ceded to it, and started the Swedish-Bremen wars in 1653/54. The treaty also delegated the determination of the Swedish-Brandenburgian border in the Duchy of Pomerania to the parties. At Osnabrück, both Sweden and Brandenburg had claimed the whole duchy, which had been under Swedish control since 1630 despite legal claims of Brandenburgian succession. While the parties settled for a border in 1653, the underlying conflict continued. The treaty ruled that the Dukes of Mecklenburg, owing their re-investiture to the Swedes, cede Wismar and the Mecklenburgian port tolls. While Sweden understood this to include the tolls of all Mecklenburgian ports, the Mecklenburgian dukes as well as the emperor understood this to refer to Wismar only. Wildeshausen, a petty exclave of Bremen-Verden and fragile basis for Sweden's seat in the Westphalian circle diet, was also claimed by the Bishopric of Münster. Bavaria retained the Palatinate's vote in the Imperial Council of Electors (which elected the Holy Roman Emperor), which it had been granted by the ban on the Elector Palatine Frederick V in 1623. The Prince Palatine, Frederick's son, was given a new, eighth electoral vote. The Palatinate was divided between the re-established Elector Palatine Charles Louis (son and heir of Frederick V) and Elector-Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, and thus between the Protestants and Catholics. Charles Louis obtained the Lower Palatinate, along the Rhine, while Maximilian kept the Upper Palatinate, to the north of Bavaria. Brandenburg-Prussia (later Prussia) received Farther Pomerania, and the Bishoprics of Magdeburg, Halberstadt, Kammin, and Minden. The succession to the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, whose last duke had died in 1609, was clarified. Jülich, Berg, and Ravenstein were given to the Count Palatine of Neuburg, while Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg went to Brandenburg. It was agreed that the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück would alternate between Protestant and Catholic holders, with the Protestant bishops chosen from cadets of the House of Brunswick-Lüneburg. The independence of the city of Bremen was clarified. Barriers to trade and commerce erected during the war were abolished, and "a degree" of free navigation was guaranteed on the Rhine. Legacy The treaty did not entirely end conflicts arising out of the Thirty Years' War. Fighting continued between France and Spain until the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659. Nevertheless, it did settle many outstanding European issues of the time. Some of the principles developed at Westphalia, especially those relating to respecting the boundaries of sovereign states and non-interference in their domestic affairs, became central to the world order that developed over the following centuries, and remain in effect today. In several parts of the world, however, sovereign states emerged from what was once imperial territory only after the post-World War II period of decolonization. More significantly, one of major principles—the balance of power—was undermined in the Twentieth century. Referring to the Soviet Union, Adolf Hitler said: Without Wehrmacht, a “wave would have swept over Europe that would have taken no care of the ridiculous British idea of the balance of power in Europe in all its banality and stupid tradition—once and for all.” During World War II, the multipolar balance became bipolar, between the Axis and the Allies, followed by the United States and NATO nations against the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact nations during the Cold War. (1967: 332) His chapter, titled “The New Balance of Power,” Hans Morgenthau opened with the words: The destruction of that intellectual and moral consensus which restrained the struggle for power for almost three centuries deprived the balance of power of its vital energy that made it a living principle of international politics … The most obvious of these structural changes which impairs the operation of the balance of power is to be found in the drastic numerical reduction of the players in the game.” After the fall of the Soviet Union, power was seen as unipolar with the United States in absolute control, though nuclear proliferation and the rise of Japan, the European Union, the Middle East, China, and a resurgent Russia have begun to recreate a multipolar political environment. Instead of a traditional balance of power, inter-state aggression may now be checked by the preponderance of power, a sharp contrast to the Westphalian principle. +

|